»Flint & Straw« Interview

Elephant No. 6

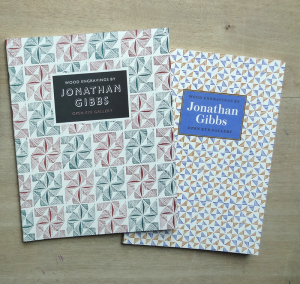

Jonathan Gibbs has been an artist and illustrator for two decades. His work ranges

from abstract painting to wood engravings, in which he depicts landscapes and everyday objects. Over the years, he has balanced his art practice with the demands of a full-time teaching position as Head of Illustration at Edinburgh College of Art. In an introduction to a recent exhibition Jonathan Gibbs’ work was described as »summary

of Englishness«. The artist says he takes this as a complement, though he is still not sure exactly what that means.

When did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

There was no decision, but I knew what I wanted to do. It was Mrs Hubbins who first spotted my artistic inclinations. She was my primary teacher during early school days, and my parents gave complete encouragement from the start. When I was aged nine or ten, …

… Miss Lamb was the great inspiration, a wonderful teacher. She was a remarkably pale, white-haired lady who wore clear-rimmed spectacles and bright orange lipstick. Later, Donald Potter taught me sculpture with robust and critical advice.

Before carving, he would make a folded-and-squared paper hat to keep the stone dust out of his hair, as Eric Gill had taught him. In retrospect, I owe everything to these schoolteachers.

How did you find going to university in London?

From Lowestoft School of Art I went to the Central School of Art and Design. With no previous experience of London, my mind was opened to many different approaches to drawing and making things — a revelation. I studied painting from 1973 to 1978, finishing as a postgraduate at the Slade School of Fine Art. There were many artists who lectured in the London art schools, and students could visit studios and exhibitions by those that taught them. At the Central, Adrian Berg was a great help to me. He invited David Hockney to one of our student exhibitions. This was momentous, a deeply impressive event. Hockney wore a baggy suit with a long mackintosh and stood in the centre of the room, smoking, and he spoke with us about the exhibition and about our work. During the early 1970s Butler’s Wharf was just beginning and we met various artists who inhabited warehouse studios beside Tower Bridge and in the East End. We noted that Derek Jarman slept amongst cushions in a small greenhouse placed in the middle of a vast studio space high above the Thames. This was quite something.

What is the most important thing you learned while at university?

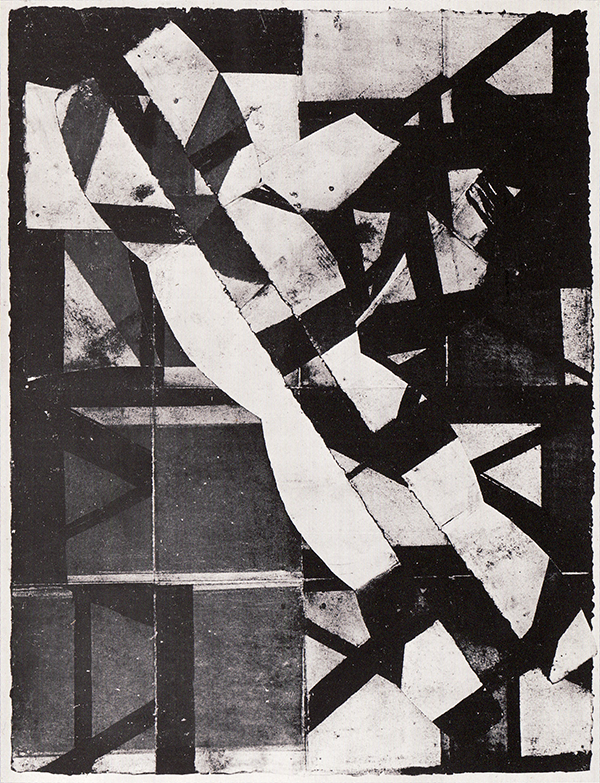

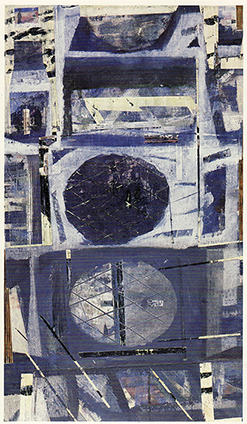

One had to find a path from disparate influences and varied tutorial advice. For me drawing was the dominant element. My work was abstract; concerned with materials, surface, and structures in space.

I drew from landscape and the human figure and this continues to be so, in a way, all these years later. I was reasonably confident, rather resistant to advice, probably, and became quite independent. The Slade was rigorous, leading one to question and analyse everything — every aspect of one’s work. My academic experience there formed the basis for everything that has followed. My work was monochromatic: charcoal, graphite, paper linen or canvas… black and white with very occasional use of red, blue or grey… This is still the case, actually.

When did you discover wood engraving?

Blair Hughes Stanton taught at the Central, as did Norman Ackroyd, so I was aware of the process, as well as etching and drypoint. But I began to engrave seriously in about 1982 or 1983, during which time I was teaching part-time, drawing, painting and exhibiting. This remains the balance, although life has become rather more complicated. I had a collection of tools and blocks and tried using them as an experiment. I had been making scratched drawings into heavily chalked paper, so it seemed a natural progression to carve into wood surfaces, taking impressions by hand. I began and could not stop. There was

no glimmer of illustration at this stage. That happened later, in 1986.

How does this technique appeal to you?

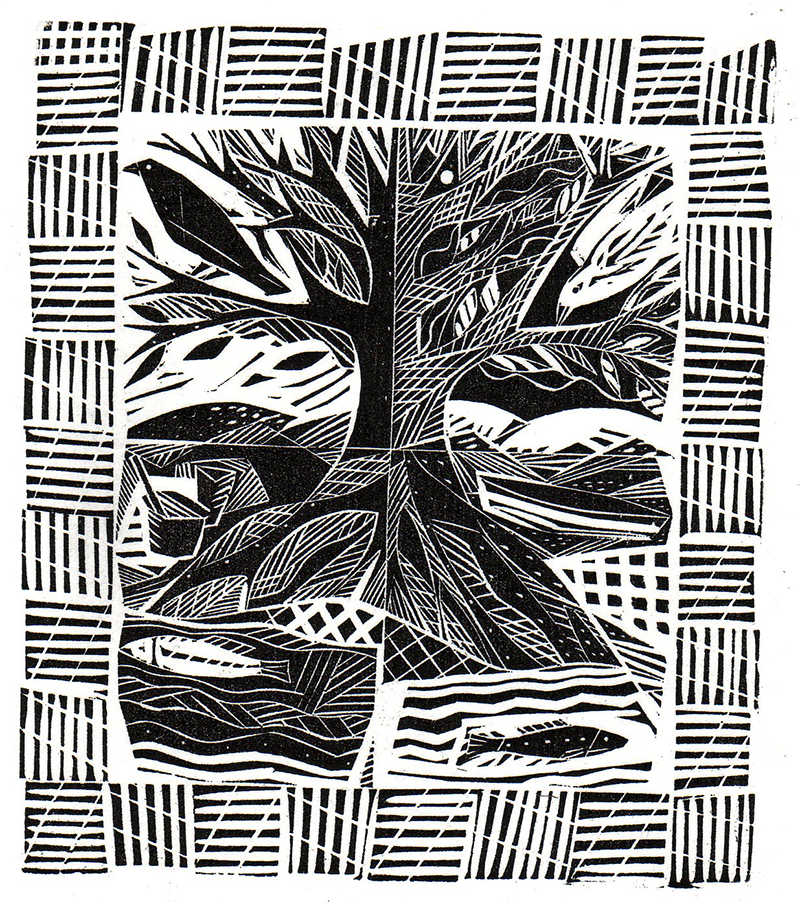

It enables me to be an illustrator, the scale suited to making imagery for the page, as well as giving natural extension to my ideas in painting and drawing. As a graphic medium it also involves sculptural concerns with tools and wood, and the coordination of hand and eye.

This way of working appeals to me very much and a stream of imagery continues to flow, which I greatly enjoy. The tactile process gives me great fulfilment. Everything about it: the preparation, cutting and carving of a wood block to printed directly and quickly, by burnishing with a bone spoon. It is kitchen table technology, so that some impressions can be a little inexact or rough. But I like this. I use a press from time to time for printing editions.

Is it art or craft?

I would not make that distinction. However, it is a fascinating question. It seems to me that every image or object has to made somehow. How is this to be done? I have concentrated on various ways, taking considerable pains in preparation and in the creative process. I would say that there has to be great skill in the making. It concerns the mind and heart, as well as any manual facility.

I look at artworks to understand how they are made in relationship to their spirit and meaning, a connection that intrigues me very deeply.

How do you choose your subjects?

Working as an illustrator, the choice is given. It is a very direct discipline as one is commissioned purely for the quality of the work. I like this directness and am inspired by the continuously varied collaboration with editors, designers, art directors and publishers. Ideas are questioned and renewed by every brief. There is much freedom in the interpretation, but one works with the editor or designer to make this possible, always for an intended context. And deadlines can focus the mind.

Alongside this activity, I work in series of drawings and ideas to be engraved. Currently these depict great rivers, whales and elephants, for some reason… Vistas of landscape. My methods have been fairly constant for twenty-five years. However, the character of the work changes. For exhibitions I will develop sets of work, giving a narrative to a range of imagery, in various media. I exhibit new work every two or three years.

Does wood engraving limit what you can represent?

I feel that the limitations will lie within one’s ability to draw something,

not in the medium. Certainly, I am rather limited: I like to depict fish, with the occasional tree.

How do you find teaching?

Art colleges have been very good to me and I feel greatly privileged to be involved with the education of students. I started early on, as a part-time lecturer. My goodness, I was inexperienced in 1979; that was the beginning of it all and I did my best. Teaching causes one to question everything and define one’s artistic principles and ideas. I hope that I have become more informed and convinced in some of these. Creative work informs my teaching at every level, very directly, always. It enables me actually to talk with students with some confidence. Nevertheless, I suspect that I may repeat myself and make obscure comments from time to time and have been told that students cannot always tell whether or not I am being serious. It is hard to be sure of this. I shall try to retain this air of mystery.

What is the message you try to get through to your students?

Perhaps I should use a megaphone. Do you require the long or short answer?

Or perhaps some course documents at this point of the interview…

There is no message but there are conversations, texts, lectures, subjects and methodologies that should be studied over a number of years, of course. One tries to impart the spirit of creativity, in various approaches to theory and practice. This reads as being rather pedantic, I suspect, but I continue to study as both an artist and lecturer, passing on academic knowledge and professional experience to students: all that I know of this life. As someone has said,

»this is simple, but it is not easy.«

Does teaching leave you enough time to develop your own work?

I have no complaints. I rise very early in the morning and do something before travelling into college, also in the evening and the weekends. I have a small room at home, full of stuff: a plans chest, printing-press, painting and drawing materials, reference books, collections of stones and bones — flotsam and jetsam. Everything is ordered rather obsessively; either piled up or filed away. There is a computer and a couple of acoustic guitars. I work on a small kitchen table set against the window. This faces south and the light is good — everything flows from this workspace. The work is somewhat intermittent but highly focused, out of necessity. On holiday I make drawings: landscapes, objects, windows and doorways. My engraving stuff fits into a small suitcase: tools, sandbag, roller, ink and paper.

I heard your work described as »the summary of Englishness«.

How do you feel about that description?

I think that this is a complement. Thank you. But I am not sure what on earth it means. I am an Englishman. That much is true. I have lived and worked in Scotland for twenty years; perhaps this accentuates the Englishness. Another description might be »modern British: art and design from a small island«. All my work has been informed by my origins: family and place, architecture and the forms of nature in East Anglia with its particular qualities of light, the flint and straw.